Science and Stones

Deep inside massive stars, pairs of newly-manufactured oxygen-16 atoms fused, each pair transforming into an atom of silicon-28, an atom of helium-4 and some energy. Thus began the story of the universe's stones.

Though not as chemically versatile as the carbon-based molecules of life, minerals based on the stable silicon-oxygen-silicon bonds are typically hard, strong and durable. The stability and abundance of these silicate-based stones means that they form the bulk of stony planets like the Earth. And, although these stones' liability to brittle fracture limits their technological uses, this property allowed our ancestors to fashion stone tools thereby developing the technological skills that today gives us appliances of science like washing machines and iPads.

Apart from these universal stones made of silicate minerals, the Earth has its own special stones. They are the carbonate stones, composed of minerals such as calcite and dolomite that chiefly consist of carbon, oxygen, calcium and magnesium. Small deposits of such carbonate minerals may occur on Mars, but they haven’t yet been found on other planets in the solar system.

NGC 6543, the Cat’s Eye Nebula, in Draco. As in the Eskimo Nebula in Gemini, these intricate shells of glowing ionized gas were expelled from a central star system. The ionized gas includes atoms of nitrogen, oxygen, silicon and magnesium made inside the central stars.

Credit: Hubble Space Telescope, NASA/ESA

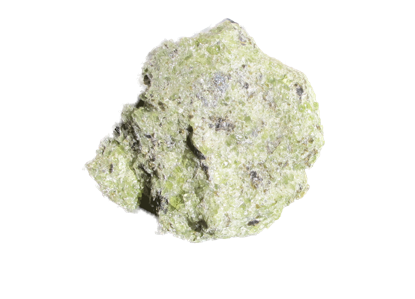

This stone from the Earth’s mantle was ejected by a volcano in Lanzarote, Canary islands in the 1730s. It is mostly made of the green silicate mineral olivine. High-magnesium olivines like this consist chiefly of oxygen, silicon and magnesium atoms made deep inside stars like those at the centre of the Cat’s Eye nebula.

Stone collected and photographed by Tom Williamson

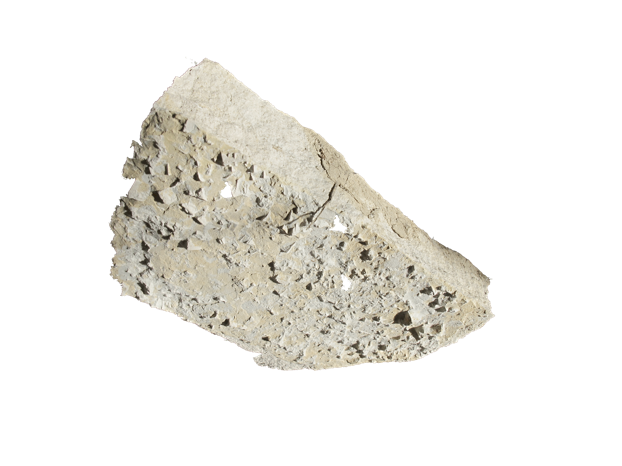

This carbonate stone from a quarry on the Isle of Portland, England is a pure oolitic limestone, consisting chiefly of oxygen, carbon and calcium. The cubes projecting from it’s lower surface are limestone casts of halite (sodium chloride) crystals.

Portland stones are easy to carve and resist decay in polluted urban environments like that of historical London. They were first used to build new Italianate classical buildings in London by famed British architect Inigo Jones (below) and his colleague, the mason and sculptor Nicholas Stone.

Courtesy: Albion Stone Quarries Ltd, photo by Tom Williamson

Interior of the Pantheon, Rome, by Giovanni Paolo Panini (

Interior of the Pantheon, Rome by Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765). The beautiful stones of the Pantheon, some based on silicates and others on carbonate minerals, were imported at great cost from imperial quarries in distant provinces like Egypt. When Inigo Jones visited Rome in 1614 with Lord and Lady Arundel, he was deeply impressed by these stones and grasped their unique ability to speak of a ruler’s vast imperial reach.

How Nicholas Stone and his father-in-law, the Amsterdam city mason Hendrick de Keyser, collaborated with Inigo Jones in introducing the large-scale usage of Portland Stones to London.

(new link under construction)

Portrait of Inigo Jones painted by William Hogarth in 1758 after a 1636 painting by Sir Anthony van Dyck.

Inigo’s Stones

A London Welshman who fell in love with Italy, Inigo Jones rose from humble beginnings to become the famed ’Architect of Great Britain’, friend of masons, kings and queens and foe of Ben Jonson and Thomas Wentworth, first earl of Strafford.

Apart from one recent biography by a journalist, Inigo’s story has hitherto been the preserve of historians of art and architecture. Yet stones, the masons who carved and understood them, the aristocrats who owned them, the ruined stones of Rome, the giant monoliths of Stonehenge, the creamy stones of Portland, the distant marbles of Ireland, played an important part in Inigo’s life.

Living on the Isle of Portland, near the cliff-side quarries that Inigo and the mason Nicholas Stone revitalised in the early 1600s, Tom became fascinated with the multifaceted story of Inigo’s stones. A book on the subject will be published shortly.

How deep, wet, porous stones could magically save the world. More here.